· Agentic AI · 8 min read

The Blackboard Architecture: Solving the Agent 'Phone Game'

Chains are brittle. We need a shared state object for robust multi-agent reasoning.

If you have ever tried to build a Multi-Agent System (MAS) using the standard tutorials that dominate the internet today, you have almost certainly run face-first into the “Phone Game” problem.

The predominant architectural pattern right now is the Linear Chain. The orchestrator tells Agent A (The Researcher) to go find the data. Agent A gathers a bunch of raw information, formats it down into a neat string, and passes that string as a message payload to Agent B (The Analyst). Agent B reads the message, adds its own critical context, summarizes the findings, and passes that new string to Agent C (The Writer).

By the time the final output reaches Agent D (The reviewer) or the user’s screen, the original nuance of the data is completely lost. Important context has been halllucinated away in the summaries. The final instruction has morphed into something entirely unrecognizable from the original prompt.

Worse, Linear Chains (A -> B -> C -> D) are incredibly brittle from an infrastructure perspective. If Agent B’s API request times out, or if it encounters a transient error and drops a critical detail from its output, the entire chain downstream starves and collapses. You end up writing hundreds of lines of complex Python just to handle retries and error routing for a single, rigid sequence of events.

This isn’t autonomy. It’s an obstacle course.

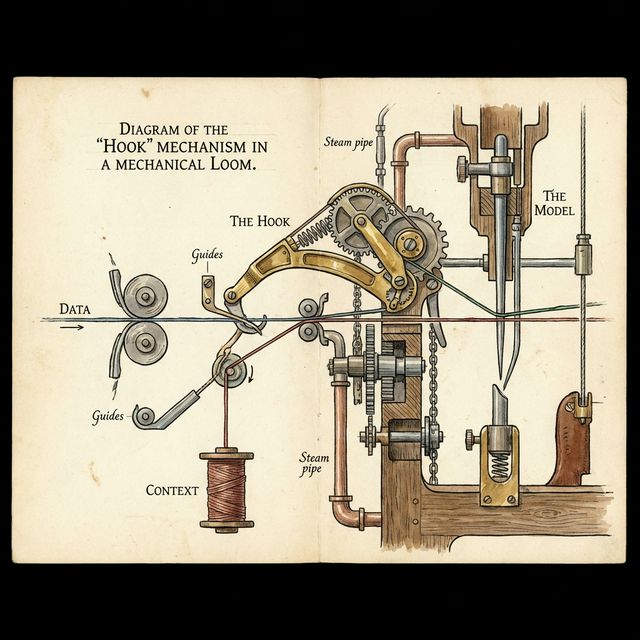

There is a significantly better way to build these systems. It is not new. It’s a foundational pattern from AI research in the 1970s that is making a massive, necessary comeback right now in the era of LLMs: The Blackboard Architecture.

Re-Centering the Flow: The Board

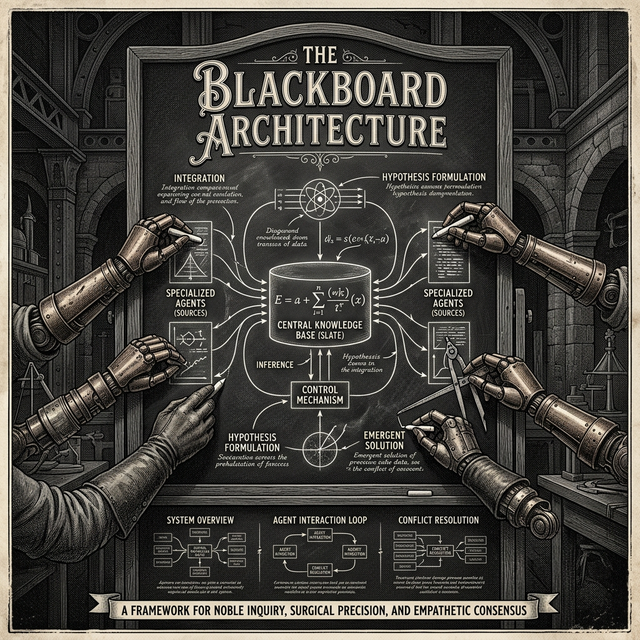

In a Blackboard architecture (which was recently highlighted and rigorously tested in a major new paper: arXiv:2507.01701), agents absolutely do not talk to each other directly. They do not pass messages.

Instead, they all talk to the Board.

To understand this, you need to break the architecture down into its three core primitives:

- The Blackboard: This is a shared, globally accessible state object. It contains the current problem definition, all intermediate partial solutions, ongoing hypotheses, and the final goal criteria.

- The Knowledge Sources (Agents): These are your specialized LLM workers. You might have a “Code Debugger,” a “Log Analyzer,” and a “Documentation Writer.” They do not know about each other. They interact solely by watching the board.

- The Control Shell: This is the orchestration mechanism. Often a very lightweight, fast model (or even deterministic code), the Control Shell decides which Knowledge Source gets permission to write to the board next, based on the board’s current state.

Think of it like a team of highly specialized Site Reliability Engineers standing around a physical, massive whiteboard during a severity-1 outage.

At timestamp 0, the Incident Manager writes the critical problem on the board: “The primary auth system is throwing 500s.”

The Database Admin steps up to the board. “I checked the Postgres logs; we have slow queries accumulating on the Sessions table.” (They write this observation on the board).

The Backend Developer reads the new note on the board. “Oh, if the Sessions table is locked, the Auth microservice will timeout waiting for a connection.” (They write this hypothesis on the board).

The Incident Manager sees the hypothesis. “Approved. DB Admin, deploy the emergency index on the Sessions table.” (They write the action item on the board).

Notice what didn’t happen here. The DB Admin did not send a direct Slack message to the Backend Developer. They both simply reacted to the evolving, shared state of the board.

The Unbeatable Benefits of Shared State

Moving away from Linear Chains and adopting the Blackboard Architecture provides three massive operational advantages when deploying agents into production environments like Google Kubernetes Engine (GKE).

Benefit 1: Asynchronous Contribution and Resilience

In a message-passing chain, agents block each other. Agent B cannot start until Agent A finishes completely.

In a Blackboard system, the agents can contribute asynchronously. A slow “Researcher” agent can continuously dump new findings onto the board in real-time. Meanwhile, the “Writer” agent can be simultaneously drafting sections of the report based solely on what is currently available on the board.

If the Researcher finds a new, conflicting fact, they update the board’s state. The Writer agent, designed to react to state changes, sees the new fact and dynamically revises the draft paragraph.

If one agent crashes or gets rate-limited by its LLM provider, the system does not halt. The other agents continue working with the state that is available. Resilience is built in at the architectural level.

Benefit 2: The Economics of Context

If you run a classical message-passing MAS, you will quickly discover that you are burning an obscene amount of money on tokens. Why? Because to prevent the “Phone Game” degradation, you usually end up copying the entire, massive conversation history and shoving it into every single prompt for every subsequent agent in the chain. You are forcing the LLM to re-read everything just to preserve context.

With a Blackboard, the context is centralized and structured. The agents do not need the entire raw transcript. They only need to read the specific sections of the board that are relevant to their specialization.

The paper (arXiv:2507.01701) cites massive token reductions and efficiency gains because the orchestrator is passing pointers to state rather than the entire raw history. In the age of expensive inference, context economy is everything.

Benefit 3: Dynamic Selection (Emergent Workflows)

This is the killer feature. You do not need to hard-code a brittle workflow logic tree in your application code.

The Control Shell simply looks at the current structured state of the board and asks a routing question: “Given what we know right now, who is the most useful specialist to activate?”

- If the board contains raw code but no test outputs -> The Shell activates the QA Agent.

- If the board contains a failing test output -> The Shell activates the Debugger Agent.

- If the board contains code, passing tests, and approved status -> The Shell activates the Deploy Agent.

The workflow is not dictated; it emerges naturally from the state of the problem. This is how you handle complex, ambiguous tasks where the exact steps needed are unknown at the start.

Implementing the Blackboard in Code

You do not need a specialized PhD or a proprietary framework to build this. You need a rigorously defined, structured schema. The Blackboard should never just be a massive, unstructured string of text. It must be a structured JSON object.

If you are building this on Google Cloud, your Blackboard is likely living in a fast, globally consistent data store like Cloud Spanner or Redis Memorystore, allowing multiple agent instances (running as separate pods in GKE) to read and write safely.

Here is a simplified TypeScript interface of what that state object might look like:

interface BlackboardState {

objective: string;

globalStatus: 'PLANNING' | 'EXECUTING' | 'REFINING' | 'VERIFYING';

workspace: {

rawFindings?: string[];

draftCode?: string;

compilerLogs?: string;

testResults?: TestOutcome[];

};

hypothesisThread: Hypothesis[];

activeConstraints: string[];

consensusReached: boolean;

}The core loop of your application-the “Control Shell”-is surprisingly simple. It fetches this JSON object from the database, feeds it to a fast, cheap Router model (like Gemini 1.5 Flash), and asks a single question:

“Analyze this BlackboardState JSON. Based on the globalStatus and the data present in the workspace, which defined tool/agent should I invoke next to move closer to the objective?”

The Consensus Loop: Killing Hallucinations

A critical focus of the newer Blackboard implementations is the concept of the Consensus Loop.

In older MAS designs, the system accepts the first answer an agent outputs, assumes it is correct, and moves on. This is terrifying in production.

A Blackboard mandates iteration until the board stabilizes. Agent A writes a proposed code fix to the board. Agent B (The Security Reviewer) reads the board, finds a vulnerability in the proposed fix, and writes a critique. Agent A reads the critique, updates the code on the board. Agent B re-evaluates the board and marks its approval.

Only when the consensusReached flag within the Blackboard State is flipped to TRUE by the Control Shell is the system permitted to exit the loop and return the final output to the user.

This internal “Write-Critique-Refine” loop, all occurring securely on a shared state object, drives hallucination rates down orders of magnitude. The final output is trustworthy because it has been rigorously and iteratively cross-checked by specialized, adversarial perspectives.

Why the Blackboard Architecture Matters Now

We stopped using Blackboard patterns in traditional, deterministic software engineering decades ago because managing concurrent locks on shared state in highly distributed systems is notorious for causing priority inversions and Mutex hell. It was often easier to just pass clear messages.

But Large Language Models have changed the constraints.

LLMs are the locking mechanism. They are slow enough in execution, and semantic enough in their understanding, to gracefully manage the concurrency of a shared workspace without deadlocking.

We are finally shedding the “Chat” interface paradigm. We are realizing that typing into a linear, sequential log is a terrible intellectual interface for complex work. We are moving toward “Workspaces” and “Canvases”-environments where multiple entities collaborate on a shared state.

If you are building an AI product that aims to actually do work, rather than just simulate conversation, you must build a Workspace. And the Blackboard is the definitive, proven architecture of the Workspace.