· AI At Scale · 6 min read

AI Quantization and Hardware Co-Design

Explore how quantization and hardware co-design overcome memory bottlenecks, comparing NVIDIA and Google architectures while looking toward the 1-bit future of efficient AI model development.

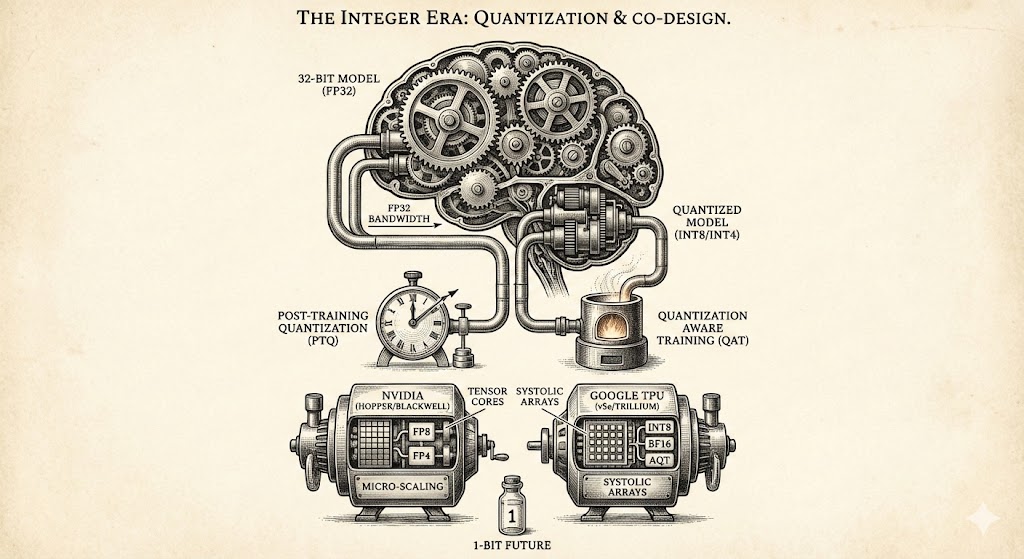

The Integer Moment

For the last ten years, the AI industry has been fighting a war of scale. The strategy was simple, brute-force, and incredibly expensive: if you wanted a smarter model, you made it bigger. You added parameters, you added layers, and you fed it more data. This was the era of “bigger is better,” and it worked. It gave us GPT-4 and Gemini.

But recently, the war has shifted fronts. We are no longer just fighting for capability; we are fighting for density. The most important question in AI today isn’t “how smart is it?” but “how much intelligence can we pack into a single bit?”

We are witnessing a “Race to the Bottom” - not in quality, but in precision. We are moving from a world where AI models “thought” in high-precision 32-bit floating-point numbers (FP32) to a world where they are increasingly thinking in 8-bit, 4-bit, and soon, perhaps, 1-bit integers.

This shift - Quantization - is not just a software optimization trick. It is forcing a complete redesign of the hardware that powers our economy. To understand where AI infrastructure is going, i spent this weekend trying to get my head around why the industry is suddenly obsessed with rounding numbers.

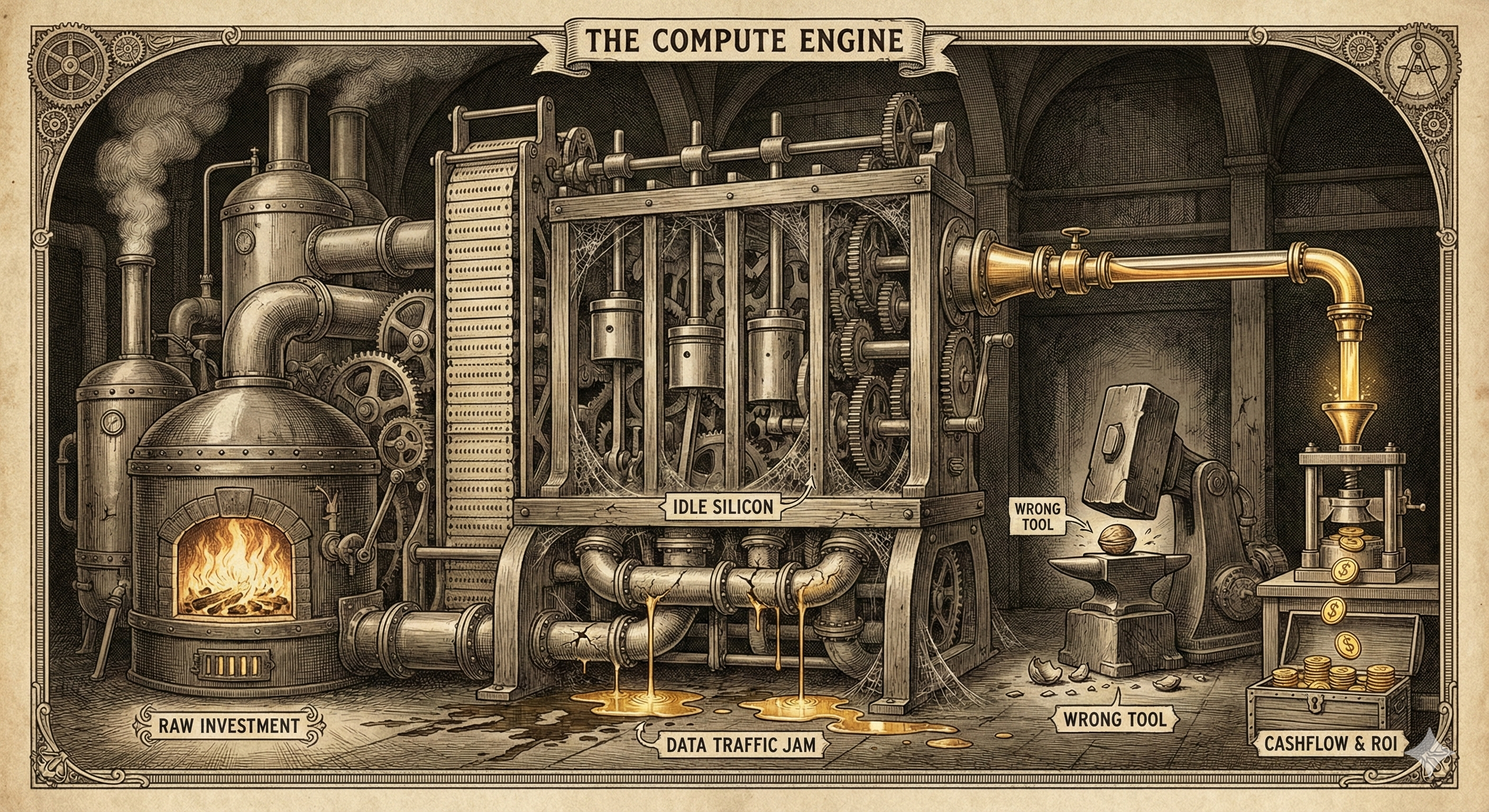

The Bandwidth Wall

To understand the problem, you have to look at the hardware. A modern GPU, like NVIDIA’s H100, is a beast. It can perform math at mind-boggling speeds. But it has a weakness: it can compute faster than it can “read.”

Imagine a master chef (the Compute Core) who can chop vegetables at supersonic speeds. But his ingredients (Data) are stored in a fridge (Memory) down the hall. It doesn’t matter how fast he chops; if he spends most of his time walking to the fridge, the dinner is going to be late.

This is the Memory Bandwidth Bottleneck. In the era of Large Language Models (LLMs), the chip spends most of its time waiting for weights to arrive from memory.

The solution is obvious: make the ingredients smaller. If you can shrink a model weight from 16 bits to 4 bits, you can carry four times as many ingredients in a single trip to the fridge. You effectively quadruple your bandwidth without inventing a new physics.

The Software “Aha!” Moment - Taming the Outliers

For a long time, we couldn’t just shrink the numbers. Neural networks were fragile. If you rounded their weights too aggressively, they became stupid.

The breakthrough happened when researchers realized why they were breaking. It turned out that LLMs have “outlier features.” In any given layer of a Transformer model, there are certain neurons that scream - they have activation values hundreds of times larger than their neighbors. When you try to compress these massive spikes into a tiny 8-bit or 4-bit grid, you lose the signal.

This led to a wave of algorithmic elegance. Techniques like SmoothQuant appeared. The idea was beautifully simple: if the activations have massive spikes that ruin the quantization, why not smooth them out? SmoothQuant mathematically “migrates” the difficulty from the activations (which are hard to quantize) to the weights (which are easy). It squashes the spikes, making the data look like a nice, uniform curve that fits perfectly into 8-bit integers.

Then came QLoRA, which proved you could fine-tune a massive model on a consumer card by using a data type called NF4 (NormalFloat 4-bit). They realized that neural network weights generally follow a Bell Curve. Standard 4-bit integers space the numbers evenly (linear), which is wasteful because most weights are near zero. NF4 clusters the quantization levels around zero, putting the resolution exactly where the information is.

Software had proven it could run intelligence on low precision. Now, it was up to the hardware to catch up.

Two Philosophies: NVIDIA vs. Google

This is where the story diverges. The two giants of AI silicon, NVIDIA and Google, have taken different paths to the integer future.

NVIDIA: The Swiss Army Knife

NVIDIA’s strategy is flexibility. They are the incumbents, and they need to support everyone - from the crypto miner to the climate scientist.

Their journey began with the Hopper (H100) architecture. They introduced FP8 (8-bit floating point). It was a safe bet; it kept the “floating point” dynamic range that developers were comfortable with but doubled the throughput. It was a massive success.

But their Blackwell architecture, takes a totally different pivot. It introduces native FP4 support. To make 4-bit math work without destroying accuracy, NVIDIA implemented Micro-scaling.

In traditional quantization, you might have one “scale factor” for a whole block of parameters. If one parameter is an outlier, it skews the scale for everyone else. Blackwell’s hardware supports fine-grained block scaling (e.g., every 16 elements). It’s like having a custom zoom lens for every tiny patch of the image. This allows them to claim 4-bit performance with near 16-bit accuracy.

Google: The Systolic Hammer

Google doesn’t sell chips; they sell services. They don’t care about legacy support or graphics. They care about “Total Cost of Ownership” (TCO) for serving Gemini.

Their TPU (Tensor Processing Unit) is built around a Systolic Array. Imagine a conveyor belt of data that flows through a grid of math units. It is rigid, hard to program, but incredibly efficient.

With TPU v4, Google stuck to Bfloat16 (BF16), a format they essentially popularized. It was safe and stable.

But with TPU v5e (“e” for efficiency), they made a hard pivot to INT8 (8-bit integer). While NVIDIA was fiddling with fancy 8-bit floats (FP8), Google bet that for pure inference, simple integers were cheaper and faster. They built the AQT (Accurate Quantized Training) library, a compiler trick that injects quantization operations directly into the training loop. They effectively said, “We won’t guess how to quantize; the hardware will teach the model to be quantized during training.”

The new Trillium (TPU v6e) doubles down on this. They increased the size of the Matrix Multiply Unit (MXU) from 128x128 to 256x256. By doubling the side length, they quadrupled the area - and thus the compute density. It is a massive, brutish integer calculator designed to crush matrix math at the lowest possible energy cost.

The Final Frontier: The End of Multiplication

If you look far enough toward the horizon, you see the end of the road: 1-bit.

Research into 1.58-bit models (BitNet) suggests we might be able to train LLMs using only three values: {-1, 0, 1}.

If this works at scale, it changes everything. Multiplication is expensive in silicon. It takes up space and burns power. Addition is cheap. If your weights are just -1, 0, or 1, you don’t need to multiply. You just add (for +1), subtract (for -1), or skip (for 0).

We could move from Matrix Multiplication Units to Matrix Accumulation Units. This would allow us to strip out massive amounts of logic from our chips, potentially improving efficiency by another order of magnitude.