· AI at Scale · 6 min read

The Compute-to-Cashflow Gap

The AI industry is shifting from celebrating large compute budgets to hunting for efficiency. Your competitive advantage is no longer your GPU count, but your cost-per-inference.

For the last few years, you could tell how well an AI company was doing by the size of its compute bill. Leaders spoke of their GPU clusters in the same way past titans of industry spoke of their factories. A large bill was a sign of ambition, of being a serious player. But I’ve noticed this is starting to change. Leaders are beginning to realize that being proud of a massive compute budget is like being proud of a high electricity bill. It’s a cost, not a victory.

The AI industry is undergoing a phase shift. The “gold rush” era, characterized by a frantic scramble for capability at any cost, is over. We are now in the era of industrialization. An era where the most important question is not “how smart is our model?” but “how much does each thought cost?” We’ve moved from celebrating raw compute to hunting for efficiency. The gap between حیرcompute purchased” and “cashflow generated” is where companies will now win or lose.

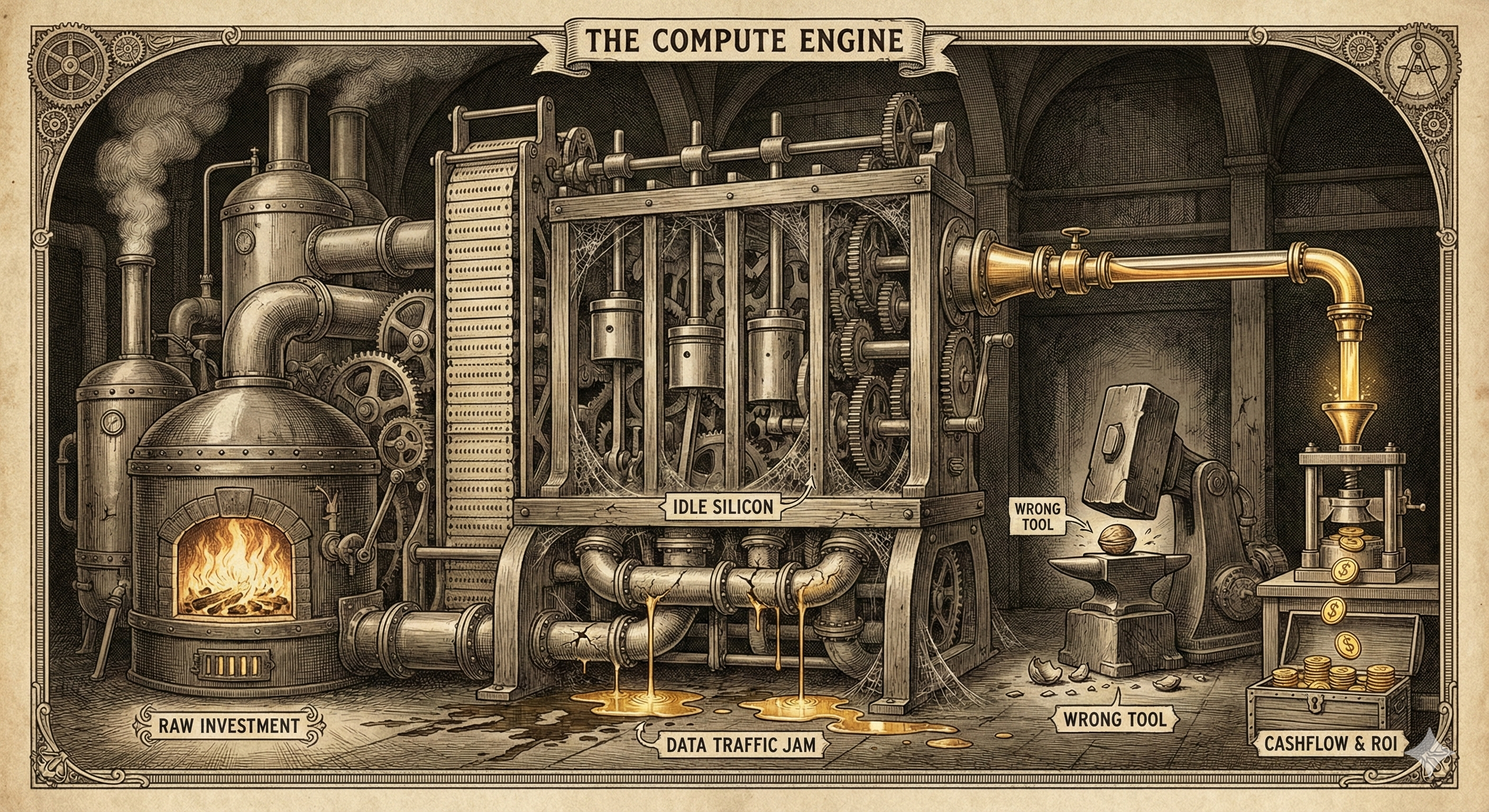

This gap is caused by a series of leaks in the system—hidden taxes on your AI budget that silently drain away capital and opportunity.

The first and most significant is the Idle Silicon Tax. This is a direct consequence of a 75-year-old problem called the Von Neumann bottleneck. In simple terms, a chip’s brain (its compute cores) is faster than its arms (its ability to fetch data from memory). Your expensive, powerful accelerator spends most of its time waiting for data to arrive. The result is that most AI hardware runs at a dismal 30-40% of its theoretical capacity. You are paying for 100% of the factory, but using less than half of it. This is a staggering waste.

The second leak is the Data Traffic Jam Tax. Moving data is expensive. It’s expensive in terms of time, and it’s expensive in terms of energy. This happens at two scales. On the chip itself, data slogs back and forth between slow main memory and fast internal caches. And between chips, the network is the computer. A single dropped packet in a training cluster of thousands of GPUs can bring a multi-million dollar operation to a standstill. You aren’t just paying for the chips; you’re paying for the impossibly complex job of keeping them all talking to each other, every microsecond.

Then there’s the Wrong Tool Tax. The market is full of different kinds of problems, but we’re often trying to solve them with a single, general-purpose tool. You wouldn’t use a sledgehammer to crack a nut. Yet, companies routinely use powerful, general-purpose GPUs for workloads where a specialized accelerator would be five to seven times more cost-effective. A recommendation engine, for instance, has a different computational shape than a large language model. Using the wrong hardware is like leaving a vast sum of money on the table, simply because you only brought one type of tool.

This problem of generality extends to the models themselves. The Bloated Model Tax is the price you pay for using unnecessarily high precision. A 32-bit number is a large, heavy brick. An 8-bit integer is a small pebble. You can carry more pebbles, and faster. The software and hardware are now smart enough to work with these smaller, lighter numbers, but many organizations have not yet made the shift. They are paying for bandwidth and memory to haul bricks when they only need pebbles.

Finally, there’s the most insidious tax: the Developer Toil Tax. Inefficient infrastructure doesn’t just waste machine time; it wastes your engineers’ time. Your most expensive and creative employees spend their days waiting for slow jobs to run, debugging obscure hardware errors, or hand-tuning low-level code. This is a soul-crushing drain on productivity and morale. It prevents your best people from doing what you hired them to do: invent the future.

The shift in focus required to plug these leaks is a move from thinking about Training to thinking about Inference. Training is a massive, one-time capital expenditure. You are building the factory. But Inference is a continuous operational expenditure that scales with your success. It is the Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) for your AI product. And in the long run, it is the cost of inference that will determine your profitability.

Plugging these leaks requires a holistic view of the system. This is where a philosophical divide in software stacks becomes a crucial business decision. The traditional approach, common with PyTorch and NVIDIA’s CUDA, is imperative. It’s like giving instructions to a cook one step at a time. It offers great flexibility, but relies on having an expert human (a “CUDA wizard”) to optimize the process.

The emerging alternative, seen with Google’s JAX and the XLA compiler, is declarative. It’s like giving the master chef the entire recipe book at the start. The compiler can analyze the whole workflow and create a perfectly optimized plan, automating away the low-level toil. This is how it consistently achieves higher hardware utilization.

More importantly, this compiler-driven approach provides what might be the most important strategic advantage of all: Hardware Optionality. Because the code describes intent, not a specific implementation for a specific chip, the compiler can retarget it for GPUs, TPUs, or whatever new accelerator comes next. In a world of volatile supply chains and geopolitical risk, being locked into a single vendor’s hardware is a strategic vulnerability. Hardware optionality is a form of compute sovereignty.

The companies that thrive in this new era will be the ones that see efficiency not as a boring cost-cutting exercise, but as an offensive weapon. An organization with a superior cost structure can be more aggressive on price, offer more generous free tiers to capture users, and reinvest the savings into a larger R&D budget. This creates a powerful, compounding advantage. It creates a cost moat.

The race is no longer to have the biggest GPU cluster. The race is to have the lowest cost-per-inference. The questions that matter are no longer about the size of your compute budget, but about the efficiency of your operations. What is your Model FLOPs Utilization? How are you matching workloads to the right hardware? What is your cost-per-inference? This is the new calculus of AI. The gap between your compute bill and your cash flow is where the battle for the future is being fought.